RMM Tools Under Attack: Exploring More Effective Detections

Remote monitoring and management (RMM) tools are software products designed to allow IT administrators to remotely monitor, manage, and troubleshoot endpoints such as servers, workstations, and mobile devices. Commonly used in enterprise environments and by managed service providers (MSPs), these tools enable tasks like patch deployment, remote desktop access, and system diagnostics without requiring a physical presence. However, their capabilities have also made them attractive to threat actors, who abuse legitimate RMM solutions to maintain persistence, evade detection, and control compromised systems.

In this research, we’ll explore the currently available detection rules for identifying the malicious use of MeshCentral by threat actors, with a focus on distinguishing legitimate activity from adversarial abuse. The RMM tool presented throughout this research has been used by threat actors in the wild, and has been signed by security researchers. Our aim was to take on the role of an attacker and configure the RMM tool (or methods of deploying the tool) to bypass the currently available detection rules, thus invalidating them. In response to the possibility that attackers can modify the way RMM tools behave, we’ll present some solutions, show you how to use more robust detections, and share system administration considerations to harden your environment against RMM use.

MeshCentral

MeshCentral is a free and open-source web-based remote computer management software. It allows users to run their own management server, either on a local network or the internet, and remotely control and manage computers running Windows or Linux. MeshCentral provides features like remote desktop, terminal access, and file management, all accessible through a web interface.

Known Attacks

MeshCentral has not been used as often as other RMM tools like AnyDesk or ScreenConnect. However, due to its status as a free and open-source solution, there’s a consistent record of attacks where threat actors have utilized MeshCentral in some way.

On April 3, 2025, Huntress published a blog on a vulnerability in CrushFTP, tracked as CVE-2025-31161. The team observed and responded to incidents where threat actors were using RMM tooling for remote access, persistence, and further post-exploitation, including AnyDesk and MeshCentral. The threat actors used MeshCentral specifically to send commands to compromised hosts and maintain persistence. Threat actors exploited the vulnerability in CrushFTP to bypass authentication and then deploy MeshCentral. Observed telemetry below:

C:\Windows\Temp\mesch.exe run

C:\Windows\Temp\mesch.exe b64exec cmVxdWlyZSgnd2luLWNvbnNvbGUnKS5oaWRlKCk7cmVxdWlyZSgnd2luLWRpc3BhdGNoZXInKS5jb25uZWN0KCczNjg3Jyk7

C:\Windows\Temp\mesch.exe -fullinstall

Immersive has two labs on the CrushFTP vulnerability, which you can visit here:

Other high-profile instances of MeshCentral being used include incidents where organizations have been compromised with CVE-2025-30406, exploiting the vulnerability to deploy encoded PowerShell scripts that download and sideload malicious DLLs. Post-compromise activity includes the use of MeshCentral for remote access and persistence. In August 2024, SOC Prime observed a significant uptick in the frequency of successful phishing attacks to gain access to Ukrainian state organizations and deploy command and control functionality using MeshCentral. Researchers note, however, that because the source code for MeshAgent is available online, UAC-0918 may have created custom malware (ANONVNC) using adapted MeshAgent source code. All the examples below show various methods used by threat actors to launch MeshAgent, the endpoint component of MeshCentral.

The first command below installs the agent fully as a Windows service:

-fullinstall

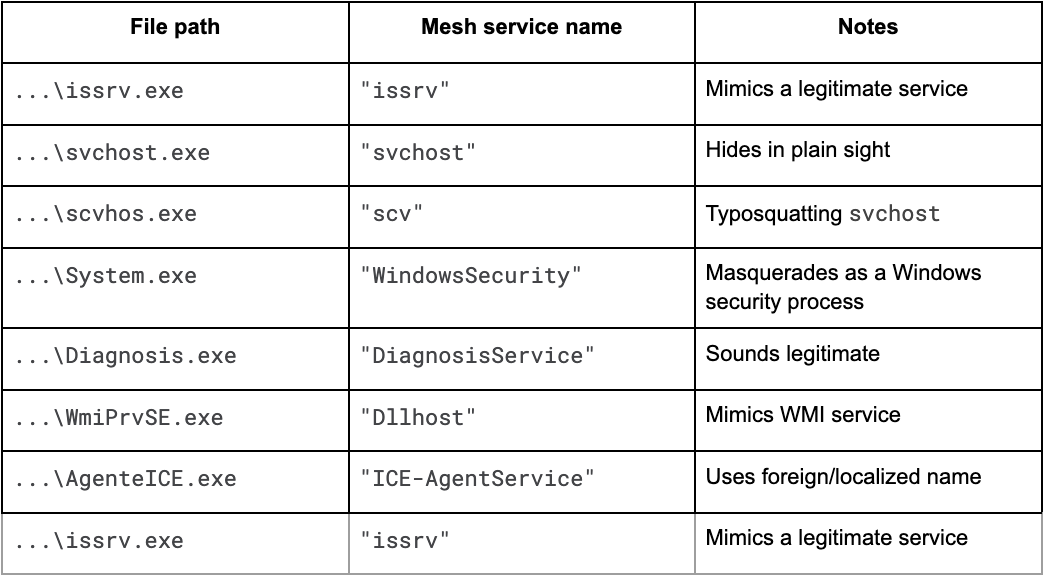

The second command sets a custom name for the Windows service that MeshAgent will register itself under. This is commonly used for stealth. The table on the next page shows some examples of service names that have been masqueraded as:

--meshServiceName="..."

The third command indicates the Windows SID of the user installing the agent, possibly for tracking or masquerading as a legitimate install:

--installedByUser="S-1-5-21-..."

Our Analysis

The MeshAgent installation process is typically straightforward, involving a single, self-contained executable that, when run, installs itself as a persistent service on the operating system. Its goal is to establish a connection back to its MeshCentral server. For an incident responder, this binary is a crucial piece of evidence because it contains a wealth of embedded information. By running a simple strings command or examining the file in a hex editor, an analyst can often extract a clear-text JSON configuration block appended to the end of the binary.

This block is a goldmine for IOCs, containing the full command and control (C2) server URL (often a wss:// address), the unique Server ID which can be used to identify other compromised devices connecting to the same C2, and other agent settings.

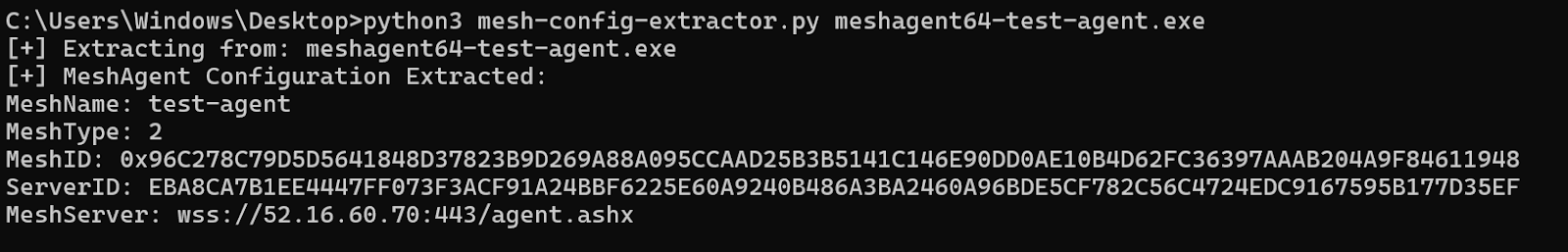

Configuration Extractor

In the event your organization uses MeshCentral and you need to quickly discern a legitimate agent from a malicious one, we’ve written a configuration extractor to use for MeshAgent to quickly work out their Mesh ID, Server ID, and Mesh Server IP address.

import re

import argparse

import os

def extract_strings(file_path, min_length=6):

with open(file_path, "rb") as f:

data = f.read()

strings = re.findall(rb"[\x20-\x7E]{%d,}" % min_length, data)

return [s.decode("utf-8", errors="ignore") for s in strings]

def extract_mesh_config(strings):

config = {}

for s in strings:

if s.startswith("MeshName="):

config["MeshName"] = s.split("=", 1)[1]

elif s.startswith("MeshID="):

config["MeshID"] = s.split("=", 1)[1]

elif s.startswith("MeshType="):

config["MeshType"] = s.split("=", 1)[1]

elif s.startswith("ServerID="):

config["ServerID"] = s.split("=", 1)[1]

elif s.startswith("MeshServer="):

config["MeshServer"] = s.split("=", 1)[1]

elif s.startswith("MeshCertHash="):

config["MeshCertHash"] = s.split("=", 1)[1]

elif s.startswith("MeshInstallFlags="):

config["MeshInstallFlags"] = s.split("=", 1)[1]

return config

def main():

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser(description="Extract MeshAgent config from binary.")

parser.add_argument("file", help="Path to MeshAgent.exe or other binary")

args = parser.parse_args()

if not os.path.isfile(args.file):

print(f"[-] File not found: {args.file}")

return

print(f"[+] Extracting from: {args.file}")

strings = extract_strings(args.file)

config = extract_mesh_config(strings)

if config:

print("[+] MeshAgent Configuration Extracted:")

for k, v in config.items():

print(f"{k}: {v}")

else:

print("[-] No Mesh configuration found.")

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

When running the script, you can expect the output to appear as below:

Existing Threat Detections

To bypass existing detections created for MeshCentral, we looked at recommended threat detections online. For MeshCentral, there weren’t many existing rules at the time of writing. One of the most prevalent was a Sigma rule, which looks for Mesh process creation and command execution through MeshAgent on the target host, shown below:

title: Remote Access Tool - MeshAgent Command Execution via MeshCentral

id: 74a2b202-73e0-4693-9a3a-9d36146d0775

status: experimental

description: |

Detects the use of MeshAgent to execute commands on the target host, particularly when threat actors might abuse it to execute commands directly.

MeshAgent can execute commands on the target host by leveraging win-console to obscure their activities and win-dispatcher to run malicious code through IPC with child processes.

references:

- https://github.com/Ylianst/MeshAgent

- https://github.com/Ylianst/MeshAgent/blob/52cf129ca43d64743181fbaf940e0b4ddb542a37/modules/win-dispatcher.js#L173

- https://github.com/Ylianst/MeshAgent/blob/52cf129ca43d64743181fbaf940e0b4ddb542a37/modules/win-info.js#L55

author: '@Kostastsale'

date: 2024-09-22

tags:

- attack.command-and-control

- attack.t1219.002

logsource:

product: windows

category: process_creation

detection:

selection:

ParentImage|endswith: '\meshagent.exe'

Image|endswith:

- '\cmd.exe'

- '\powershell.exe'

- '\pwsh.exe'

condition: selection

falsepositives:

- False positives can be found in environments using MessAgent for remote management, analysis should prioritize the grandparent process, MeshAgent.exe, and scrutinize the resulting child processes triggered by any suspicious interactive commands directed at the target host.

level: medium

This threat detection has the issue that MeshAgent needs to be called meshagent.exe. We need to find a way to change the name of a binary, and this would bypass the detection. The comment about scrutinizing the grandparent process was also interesting, because that means we’d need to control the Service Name too. This threat detection is shown below:

event.category:"process" and process.parent.executable:*\\meshagent.exe and process.executable:("*\\cmd.exe", "*\\powershell.exe", "*\\pwsh.exe")

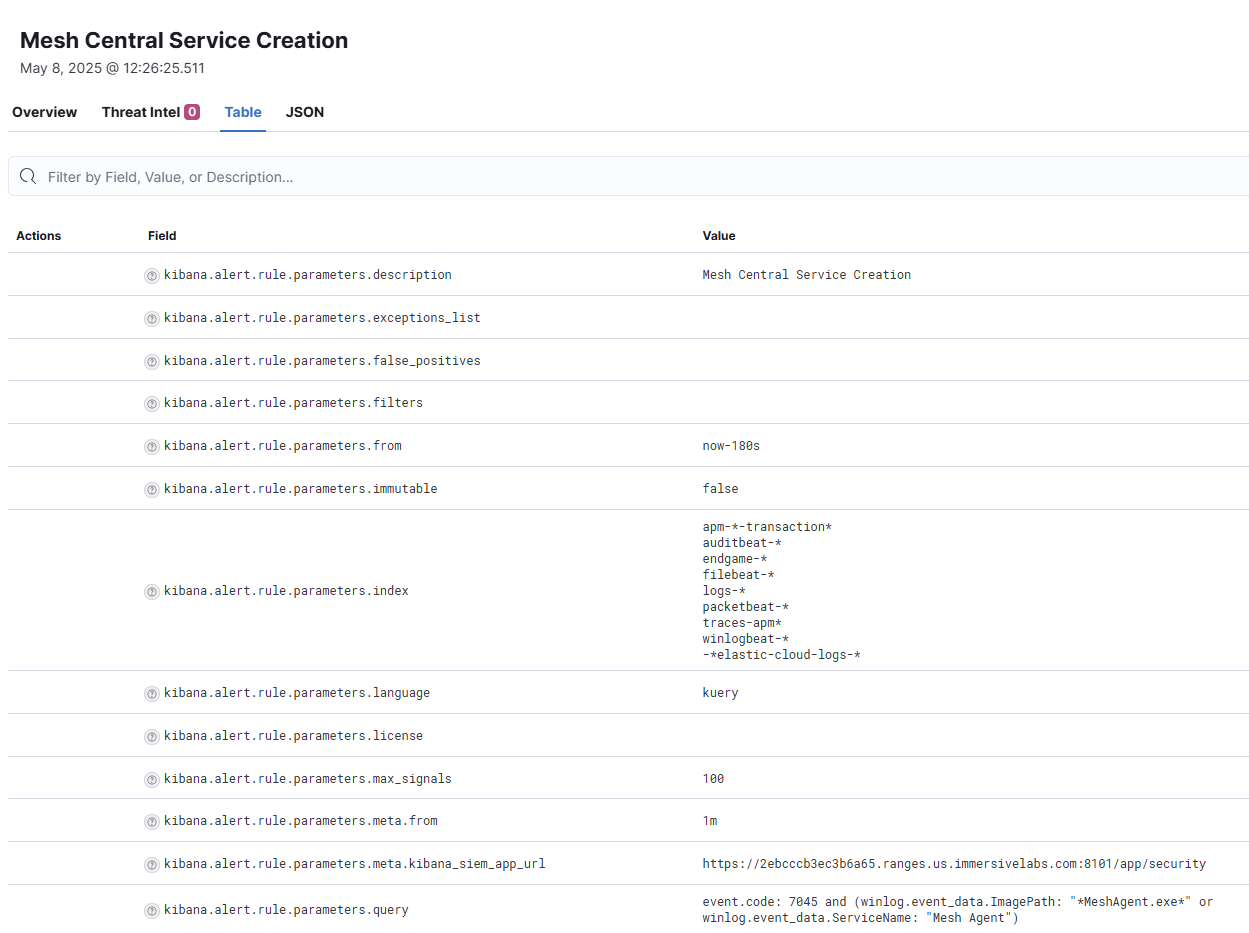

We ended up finding another rule that specifically looks for the MeshCentral service creation. The issue with this rule is the false positives that will inevitably surface if your organization is using MeshCentral more generally. The rule is below:

title: Mesh Agent Service Installation

id: e0d1ad53-c7eb-48ec-a87a-72393cc6cedc

status: test

description: Detects a Mesh Agent service installation. Mesh Agent is used to remotely manage computers

references:

- https://thedfirreport.com/2022/11/28/emotet-strikes-again-lnk-file-leads-to-domain-wide-ransomware/

author: Nasreddine Bencherchali (Nextron Systems)

date: 2022-11-28

tags:

- attack.command-and-control

- attack.t1219

logsource:

product: windows

service: system

detection:

selection_root:

Provider_Name: 'Service Control Manager'

EventID: 7045

selection_service:

- ImagePath|contains: 'MeshAgent.exe'

- ServiceName|contains: 'Mesh Agent'

condition: all of selection_*

falsepositives:

- Legitimate use of the tool

level: medium

Our Elastic instance is shown below, where we took this rule and put it into Elastic as custom rules – the plan being to run custom configurations on MeshAgent on the victim machine and see if Elastic flags the agent as malicious against the rule.

The threat detection trigger outlined in Elastic above will match if a number of key conditions are met:

- The event code is 7045 (new service has been installed)

- The ImagePath is MeshAgent.exe or

- The ServiceName is Mesh Agent

event.code: 7045 AND

(

winlog.event_data.ImagePath: "*MeshAgent.exe*" OR

winlog.event_data.ServiceName: "Mesh Agent"

)

The above rule flagged for us when we ran the default configuration and install process for MeshAgent. This rule would also trigger for nearly all installations from threat actors we observed, except if they used --meshServiceName to change the ServiceName of the installed service. However, we found another way to change the ImagePath which bypasses this detection as well.

Bypassing Existing Threat Detections

So, how did we bypass the detection? We knew we’d need a way of changing the ServiceName and/or the ImagePath during the installation process. We scoured the MeshCentral documentation to find a way of configuring the MeshAgent install, including changing the process name and service name. However, there was nothing in the documentation that led us to any information to help us change the service name. The assumption at the time was that MeshCentral didn’t have that feature because it wouldn’t be needed during normal operations. That said, MeshCentral is free and open source, so the source code is available online.

Before looking at the source code, it’s worth noting that the data we obtained from VirusTotal shows us how many different argument flags were used when installing MeshAgent.

- There were 551 instances of -fullinstall

- There were 107 instances using --meshServiceName

- The --target flag had no recorded instances of use at the time of writing

To find these arguments and attempt to bypass the detections, we began combing through the source code, looking for hidden configuration options – and found some interesting things. In the MeshAgent source code, under modules/interactive.js, there’s a section that constructs the argument list used to execute the agent in full installation mode. This logic checks whether a custom service name has been specified via the msh.meshServiceName variable. If it has, the service name is appended as an installation argument using the --meshServiceName= flag. This allows the agent to install itself under any arbitrary Windows service name, rather than using the default "Mesh Agent". Immediately after, the script prepends the -fullinstall flag, which triggers the full installation routine in the native binary. The code snippet is as follows:

if (msh.meshServiceName) {

parms.unshift('--meshServiceName="' + msh.meshServiceName + '"');

}

parms.unshift('-fullinstall');

The service installation process is orchestrated across both JavaScript and C layers, allowing the agent to be deployed under arbitrary service names.

The arguments constructed in the interactive.js snippet are passed into the native C component in meshcore/agentcore.c. There, the -fullinstall flag is parsed explicitly:

if (strcmp("-fullinstall", param[ri]) == 0)

And the custom service name is formatted and embedded:

_tf_s(startParms, ILibMemory_Size(startParms), "[\\\"--meshServiceName=\\\"%s\\\"]", agentHost->meshServiceName);

This backend logic is responsible for the actual Windows service registration and configuration. Together, the JavaScript and C layers form a flexible system that not only supports custom deployments but also introduces the potential for detection evasion, which we were able to abuse.

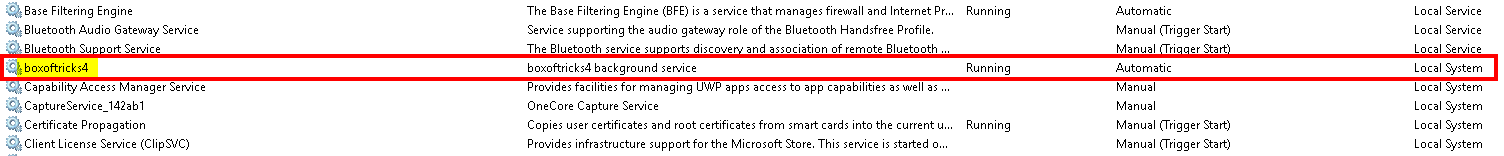

When we ran a fresh install of MeshAgent onto a simulated victim machine, we played around with various commands and argument structures based on what we’d learned, and came up with:

_tf_s(startParms, ILibMemory_Size(startParms), "[\\\"--meshServiceName=\\\"%s\\\"]", agentHost->meshServiceName);

We used a slightly playful service name “boxoftricks4” as it’s something you’d never expect to find in Windows. The installation worked, and the detections previously discussed were bypassed.

It’s also worth covering some of the recorded instances of these arguments being used to install custom-named MeshAgents. There are multiple instances of the same install method being used, recorded across VirusTotal, structured as below:

"C:\Program Files\Windowtemp\scv\scvhos.exe" --meshServiceName="scv" --installedByUser="S-1-5-21-4005801669-2598574594-602355426-1001"

The individual installing MeshAgent creates a directory path for their installation – in this case “C:\Program Files\Windowstemp\svc\svchos.exe”, with a custom service name so they can masquerade as that service. Here, the individual installing MeshAgent is trying to masquerade as the Windows Service Host (svchost.exe). Multiple instances like this exist, with the only differences being the custom service name value for --meshServiceName and the directory path. Other examples of this type of installation observed on VirusTotal include:

"C:\Program Files\Microsoft\DiagnosisService\Diagnosis.exe" --meshServiceName="DiagnosisService" --installedByUser="S-1-5-21-4005801669-2598574594-602355426-1001""C:\Program Files\donet\issrv\issrv.exe" --meshServiceName="issrv" --installedByUser="S-1-5-21-4005801669-2598574594-602355426-1001""C:\Program Files\Microsoft\WindowsSecurity\System.exe" --meshServiceName="WindowsSecurity" --installedByUser="S-1-5-21-4005801669-2598574594-602355426-1001"

So from including --meshServiceName, we know that the installation threat detection can be bypassed. However, these installations would still unpack and run as MeshAgent.exe which would trigger the threat detection looking for MeshAgent.exe executing powershell.exe or cmd.exe. To bypass the other threat detection, where the parent process is called MeshAgent.exe and it executes PowerShell or cmd, we need to find a way to change the unpacked executable name and file location. Going back to inspect the source code of MeshAgent, we saw an argument parameter called --target. In agent-installer.js, the --target can be used to tell the MeshAgent which name to install under and run as. This is perfect to bypass the parent.process.name check in one of the threat detections. In short, the --target argument requires a filename, which will overwrite the standard MeshAgent filename, as it replaces the --fileName parameter of the installer. This command will bypass both threat detections discussed in the previous section:

"C:\Users\Public\Documents\support-worker.exe" -fullinstall --meshServiceName=SupportUpdate --target=SupportUpdate

This will install the MeshAgent so it unpacks into a directory that doesn’t contain the words “MeshAgent” plus it will create the service under a different name. Finally, the unpacked binary will be called SupportUpdate.exe, which bypasses the first threat detection that looks for the parent process name being MeshAgent.exe.

New Detection Considerations

With the revelation that there are more flexible ways of installing MeshAgent onto victim machines, it’s important to think outside the box about how we detect non-standard installs of MeshAgent. If you use MeshAgent in your organization, the best idea would be to set up a naming convention and a set of parameters which are standard for the install. Also, look for the parameters --meshServiceName and --target for service name change and executable name change. That way, you can compare your known MeshAgent names (the naming convention you’ve used in your business) against other names you’re seeing.

Pick a standard naming convention for all legitimate MeshAgent installs in your organization. For example:

- CompanyMeshAgent

- MeshAgent_[Hostname]

- CorpRemoteAgent

Deploy your MeshAgent installs across your fleet using only that naming scheme, as below:

MeshAgent.exe -fullinstall --meshServiceName="CompanyMeshAgent"

Alert on any service installation where:

- Message contains MeshAgent.exe and

- The service name does not match your naming convention

One way of constructing your rule in Elastic, or other SIEM solutions, is to use a rule like:

event.code: 7045 AND Message: "*Mesh Agent*" AND NOT ServiceName: "CompanyMeshAgent*"

The rule above checks for the service creation event ID (7045), an ImagePath name containing MeshAgent.exe, while filtering out all results that share the same service name that you’d use across your company. That way, the only results will be from MeshAgent setups that you didn’t do. Unless, of course, the attacker has seen the service name you use and installed it like that. You can take this process further by testing against the signature as well. This is a robust route for detection, as any changes the adversary makes to the MeshAgent binary could potentially break the signature.

The reason attackers are using RMM tools is to take advantage of their functionality, but also their signed binary signature. The pop-up after trying to install these binaries isn’t as alarming as the red boxes when Windows doesn’t know the signature, and there are fewer red flags raised by defensive tools when there’s a recognized signature on the binary being run. If you don’t use MeshAgent at all in your environment, looking at the message and product name of the installation log that contains Mesh Agent will be enough. If they change this, the signature breaks and there are other alerts that appear in SIEMs, and hopefully your other EDR solutions.

event.code: 7045 AND Message: "*Mesh Agent*”

Ready to sharpen your detection skills? Dive into our hands-on lab and learn to spot attackers using social engineering to deploy MeshCentral for network access. Try the lab now.

Ready to Get Started?

Get a Live Demo.

Simply complete the form to schedule time with an expert that works best for your calendar.

.svg)

.webp)