Summary:

Iran’s cyber capabilities have been subject to intense scrutiny in recent years due to the high political tensions within the region. Ramped up military action and increased likelihood of Iranian cyberattacks have seen this interest spread into the mainstream media, leading to fears of cyberwarfare and deployment of destructive malware.

A review of the available research covering the history of Iranian cyber operations reveals several consistent themes:

- The Iranian cyber capability is significant but not as sophisticated as that of the US, China or Russia.

- Iran relies heavily on basic intrusion techniques, such as spear-phishing, social engineering and SQL injection.

- There is currently no information in the public domain that suggests any robust, secure networks have been demonstrably compromised by an Iranian threat actor.

Attribution of cyberattacks is difficult, and Iran has demonstrated willingness to publicize its cyber capabilities while denying responsibility for attacks attributed to it, ensuring plausible deniability by utilising proxy groups or cutouts to work on behalf of the government. As such, there is often no clear, conclusive evidence that can verify these claims. The following information, however, aims to reflect the broad consensus of the research material available in the public domain.

Background:

Iranian hacking capabilities emerged in the early 2000s, with state-aligned cyber activities appearing around 2007. In June 2009, the Green Movement (or ‘Persian Spring’) protests at the re-election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, organized heavily through Twitter, led to the Iranian Cyber Army compromising Twitters’ DNS to redirect users to a third-party site, stating ‘this site has been hacked by Iranian cyber army’.

In July 2011, an Iranian hacker breached Dutch certificate authority (CA) DigiNotar (named Operation Black Tulip), which allegedly facilitated the Iranian government spying on Google users in Iran through a man-in-the-middle style attack using fraudulent certificates.

- New York Times reporter David Sanger announced that Iran was the target of a joint operation by the US and Israel known as ‘Olympic Games’ in 2007, where the Stuxnet malware was used to sabotage components of the Natanz uranium enrichment facility, destroying 1,000 centrifuges and causing a one-year setback to Iran’s nuclear progress.

- Attackers targeted Iranian oil infrastructure using the Flame malware, described as an ‘industrial vacuum cleaner for sensitive information’, and Wiper, designed to destroy data so effectively that no code sample of it has ever been publicly disclosed.

- The Mahdi spyware that attackers unleashed across Iran, Israel and Afghanistan was discovered by Kaspersky Labs and Seculert. The firms stated that it relied entirely on social engineering techniques for distribution.

- Operation Ababil, a massive distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attack on financial institutions in the US, took place – associated by the FBI to the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps.

- Attackers targeted Saudi Aramco and RasGas using Shamoon malware (also known as Disttrack), which wiped the master boot records and replaced them with an image of a burning American flag. The group, AKA Cutting Sword of Justice, took responsibility and were attributed to Iran by US intelligence.

In 2013, the announcement of nuclear negotiations around the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action between the US, China, Russia, UK, France, Germany and Iran led to a reduction in publicized cyber activity in the region. This was despite documents that Edward Snowden leaked regarding operation BOUNDLESSINFORMANT, which showed that Iran was one of the most surveilled countries in the world, with billions of internet and telephone records collected by the US and partner agencies.

Cyber activities seemingly resumed as of November 2016, where ‘Shamoon v2’ was found targeting Saudi Arabian companies in the industrial and energy sectors. W32.Disttrack.B was broadly similar to the original Shamoon, except the image was changed to a photo of the body of Alan Kurdi, the three-year-old Syrian refugee who drowned in the Mediterranean in 2015.

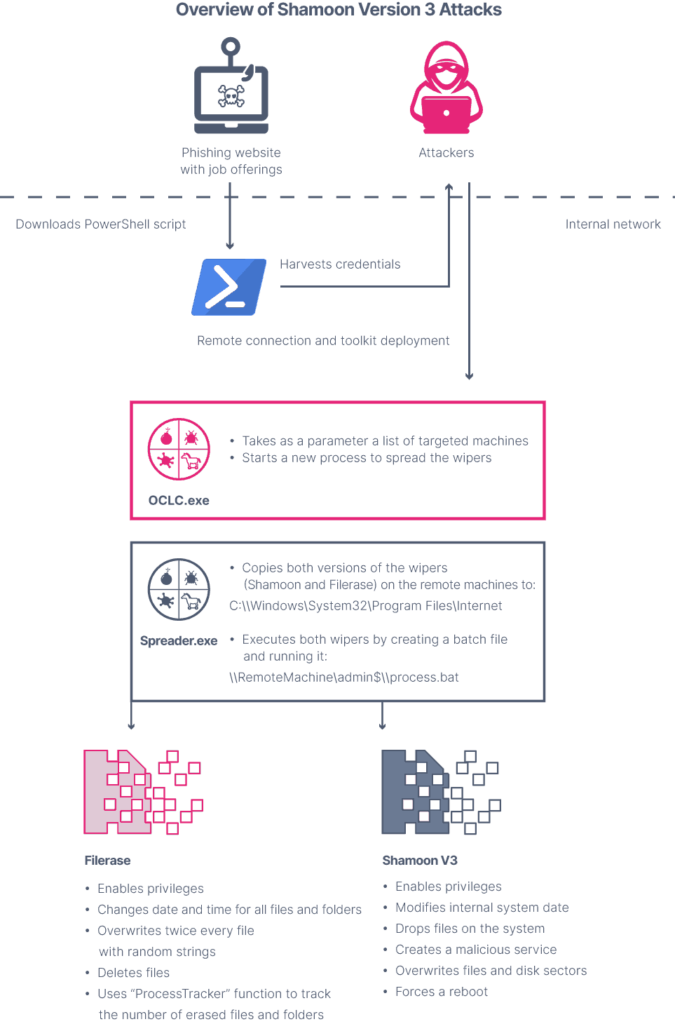

‘Shamoon v3’, discovered in 2018, affected approximately 400 servers and 100 personal computers in Italian oil services firm Saipem and at least two other organizations in Saudi Arabia and the UAE. The code was again similar to the original Shamoon but upgraded from previous versions to delete files from infected computers before the malware wiped the master boot record.

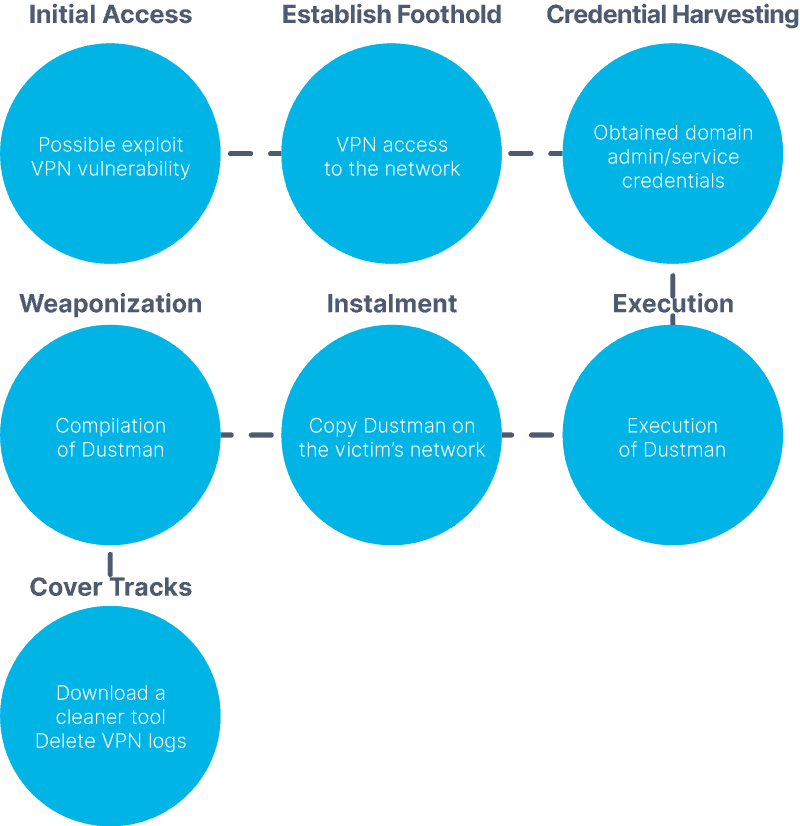

A December 2019 report from the Saudi National Cybersecurity Authority indicated that the Dustman malware strain, deployed on 29th December 2019 against Bahrain’s national oil company Bapco, appeared to be an upgraded version of ZeroCleare.

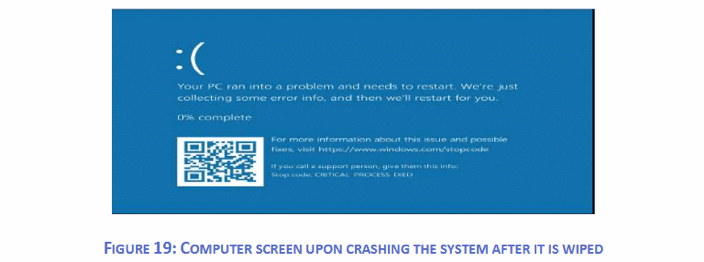

It would also appear that spear-phishing was not used in this attack, and ‘remote execution vulnerabilities in a VPN appliance, disclosed in July 2019’ were exploited to gain entry to the network instead. Successful attacks resulted in wiped systems showing a Blue Screen of Death (BSoD) message.

Image: Saudi Arabia CNA – https://www.scribd.com/document/442225568/Saudi-Arabia-CNA-report

Image: Saudi Arabia CNA – https://www.scribd.com/document/442225568/Saudi-Arabia-CNA-report

Iranian Tactics:

Despite causing significant impact, Iran’s operations have so far been technically simple. For example:

1 – The September 2012 DDoS attack on the US financial sector, including JP Morgan Chase and Wells Fargo, which caused millions of dollars in damage, was caused by young Iranian computer experts calling themselves Izz ad-Din al Qassam Cyber Fighters. They were able to direct nearly 140Gbps of web traffic (three times the capacity of the banks at the time) by simply compromising websites running software with known vulnerabilities. In 2016 the FBI attributed these attacks to seven Iranians with links to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps in 2016.

There is evidence that, since at least July 2014, individuals in the custody of the IRGC are forced to provide access to their online accounts and devices, which are then immediately used to conduct spear-phishing attacks associated with known threat actors. In October 2015, 46-year-old Iranian-American Siamak Namazi was arrested by the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps while visiting the country, and within hours of his arrest his Google and Facebook accounts initiated conversation with a number of his foreign policy and media contacts. Those controlling the accounts sent articles about a recent nuclear deal (with poorly written edits) accompanied by an email that required visitors to sign into a fake Google site to view the document. This credential theft attempt, in which the Gmail account of a prominent journalist was compromised for nearly two days, was linked to the Rocket Kitten APT.

There are, however, relatively few successful cases of Iranian intrusions into American and European government infrastructure, as it is widely considered that compromising such highly secure, classified networks is beyond the capability of Iranian threat actors. What has been shown is that unsophisticated attacks can be highly effective, and that they have afforded Iran the reputation of having significant cyberwarfare capabilities.

Notable Iranian APTs:

APT 33 – ELFIN

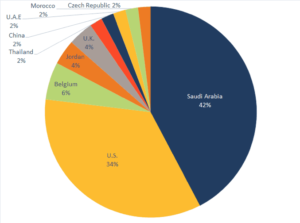

An Iranian espionage group, first active around 2014. Symantec observed that between 2016 and 2019 52% of its targets were in Saudi Arabia and 34% were in the US. The group recently attempted to exploit CVE_2018_20250 in the WinRAR application on a Saudi Arabian chemical sector target.

Commonly used credential stealing tools include LaZagne, Mimikatz, GPPPassword and SniffPass, and there is a preference for DarkComet, Quasar Rat NanoCore and Remcos Remote Access Trojans (RATs).

In one case study provided by Symantec, the following occurred over a 12-hour period:

- Target company received a spear-phishing email regarding a job vacancy;

- Target clicked the link, downloading a malicious HTML executable file that loaded content from a C&C server via an embedded iframe, and executed a PowerShell command which downloaded ‘chfeeds.vbe’ from the C&C server;

- Created a scheduled task to execute chfeeds.vbe several times a day, which acted as a downloader for a second PowerShell script (registry.ps1);

- Registry.ps1 downloaded and executed a PowerShell backdoor known as POSHC2, and then used the compromised machine to download the archiving tool winRAR.

Two days later the group installed Quasar RAT and a custom net.ftb tool, which it used to exfiltrate data to a remote host seven days later. It installed a second FTP exfiltration tool (Fastloader) two weeks later and then deployed DarkComet and several credential dumping tools before utilizing PowerShell Empire. The malicious activity continued for just over two months.

Similarly to APT33, APT39 uses spear-phishing emails but with malicious attachments or hyperlinks that result in POWBAT, SEAWEED or CACHEMONEY backdoor infections.

The group has frequently registered domains that appear to be legitimate web services and organizations relevant to its intended targets. The group has also exploited vulnerable web servers of targeted organizations to install web shells (ANTAK and ASPXSP).

The group uses Mimikatz, Ncrack, ProcDump and Windows Credential Editor for privilege escalation, and the Bluetorch port scanner and other custom scripts for internal reconnaissance. It uses archived stolen data with compression tools such as WinRAR or 7-zip. The group reportedly uses RDP, SSH, PsExec, RemCom and xCMdSvc for lateral movement, and will use custom tools such as REDTRIP, PINKTRIP and BLUETRIP to create custom SOCKS5 proxies between infected hosts.

APT 34 / OilRig / Helix Kitten

APT 34 appears to primarily use supply chain attacks on critical infrastructure targets within the Middle East. Research suggests the group uses POWRUNER, a PowerShell script that communicates with a C2 server, and BONDUPDATPR, a trojan that contains basic backdoor functionality and uses DNS tunneling to communicate with its C2 server. Some security researchers attribute this group to the Shamoon malware attacks between 2012 and 2018.

Operation Cleaver / Tarh Andishan:

Operation Cleaver is an investigation into Iranian cybersecurity capability, specifically one team they refer to as ‘Tarh Andishan’, who the report has observed targeting, attacking and compromising approximately 50 victims since 2012.

They suggest the group has targeted sensitive critical infrastructure in the US, Europe and Middle East, including military, telecoms, healthcare, oil and gas, utilities and energy producers.

The group reportedly uses either SQL injection or spear-phishing attacks as the initial method of compromise, Mimikatz and Windows Credential Editor to extract domain credentials, and Netcrawler to worm through the network. It is reported to have a strong focus on stealing confidential information and will use anonymous FTP servers, Netcat and PLink, facilitated by the TinyzBot backdoor to exfiltrate data.

Conclusions:

Iran has been the target of some of the most sophisticated malware currently seen, targeting critical infrastructure and in some cases causing physical damage. There is a research consensus that Iran has learned and developed in response to these attacks and – despite lacking the cyber skills of other more established nations –through persistence, effective use of basic techniques, and a lack of concern about its activities remaining undetected has been able to mount highly effective cyberattacks against underprepared and unsuspecting targets. However, there is limited evidence to suggest that Iran is capable of causing significant damage to sophisticated secure networks. The recent Dustman wiper does potentially represent an escalation in capability, although even in this instance, it is believed to have been distributed through a known disclosed vulnerability in a VPN service – and early analysis indicates it was a rushed, ineffective attack.

As most of the tools and tactics used by Iranian APTs are known among the cybersecurity community, Immersive Labs has already provided a number of labs to give hands-on experience of both using and defending against them.

If you already have a licence for Immersive Labs, log in and head to Objectives to try our suite of Iranian Cyber Capabilities labs. We have 17 labs to help you get to grips with everything outlined above.

Alternatively, you can try some of these labs for free with Immersive Labs Lite.