Over the last few decades, the concept of malware has undergone significant development. Its evolutionary process can tell us a lot about society and the state of the computing industry as a whole; however, even state-of-the-art attacks take elements from the tried and trusted components of early malwares – sort of like a code of best practice for hackers.

Malware evolves in various ways, but mostly via three main aspects: profit, protections, and culture. The first is perhaps the most obvious reason for an increase in sophistication; threat actors want to maximize the financial gain of an operation – just like any business would. Things get more interesting when you think about the motive of protection. Cybersecurity is a massive industry that commands extortionately high budgets to keep businesses safe from attackers all over the world. Some common protections include antivirus software, endpoint protection software, intrusion detection software, full incident response teams, vulnerability management teams, and more. This is a lot to uphold but also means attackers have a lot to circumvent, so new malwares need to evolve to get around these barriers. Thirdly, culture has a huge impact on the way malware evolves. The media plays a big part in coining new terms for types of attacks. By using frightening terms like ransomware and scareware, they increase the hype and bring an increased visibility to new types of attacks. While that does mean the population is more aware and prepared for an attack, it also attracts attackers to think of more viable avenues – much like a company reacts to market changes by altering products or increasing their range of services.

There are several ways that culture has affected the evolution of malware, but today we will look at ransomware specifically, and how it has changed over the years.

What is ransomware?

Ransomware, as its name suggests, is malicious software that blocks access to machines, systems, or artefacts until a certain amount of money is paid. Its lucrativeness has made it popular and effective over the last half-decade, but it hasn’t always been this way. In fact, this type of malware has evolved from older types, known as scareware, a method still used today that involves malicious software designed to scare someone into giving away money.

Another example of ransomware is the false blackmail. Attackers will tell their unsuspecting victim that they hold provocative, possibly reputation-damaging pictures or videos of them, and will release them on the internet to everyone they know unless the ransom is paid. Sneakily, they will include an attachment of said picture, but once opened, the pretend image will actually download, open, and install malware onto the victim’s device, with the aim of stealing data. An extremely high percentage of the time, attackers don’t even have pictures of the victim, and these people end up being part of a phishing campaign. However, it can scare a lot of people into doing what is asked of the attacker. We have a great set of labs on the topic of extortion; Kate’s Story follows a similar narrative.

The beginning

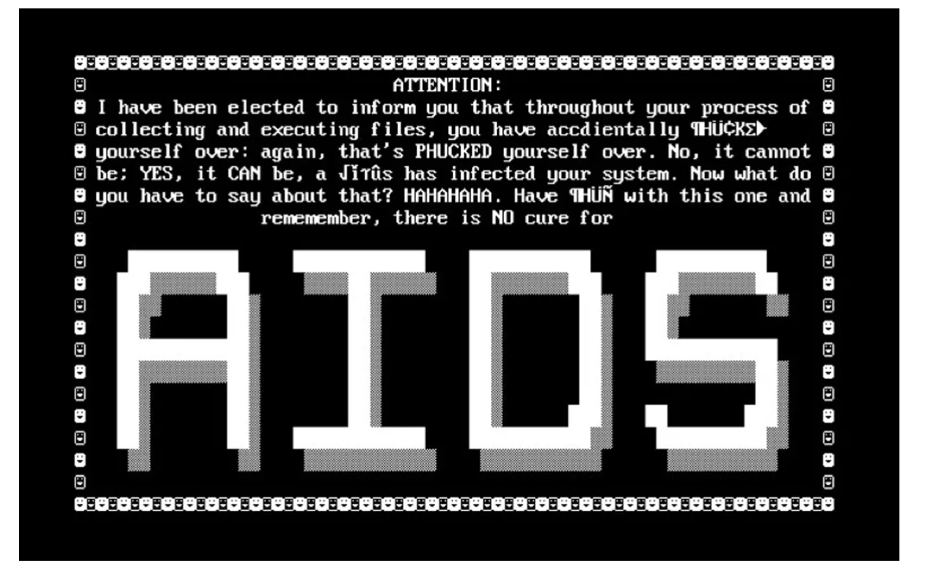

Ransomware has been around since the late 1980s, thanks to the Harvard-educated evolutionary biologist Dr. Popp. While at the World Health Organization’s AIDS conference in 1989, Popp distributed his malware, dubbed the AIDS Trojan, disguised as informational software for the event. After 90 reboots, the malware was used to encrypt data on machines and then ask the victim for a ransom. Although it began here, ransomware as we know it today didn’t take off in the mainstream until much later.

Early 2000s

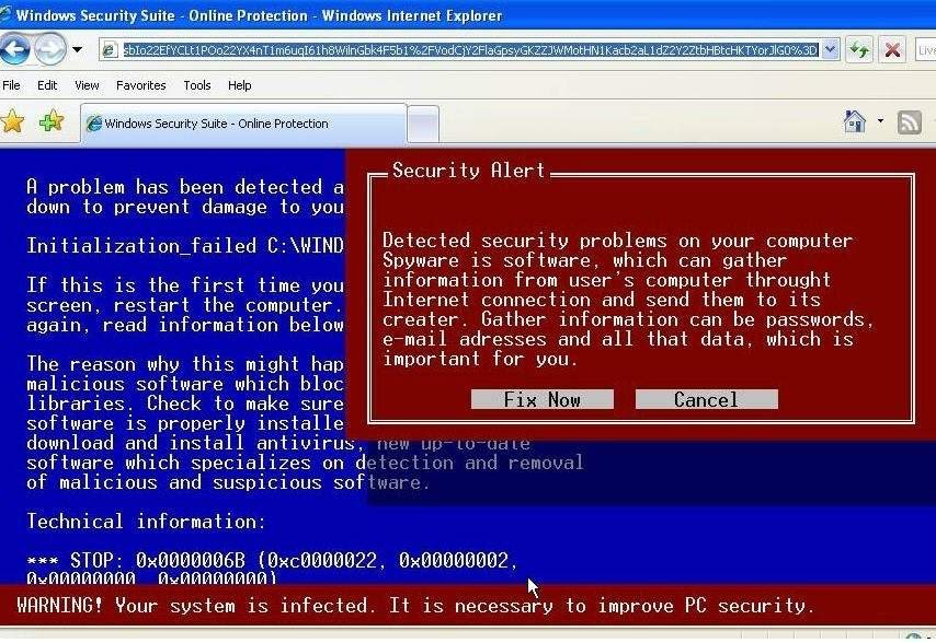

By the turn of the century, scareware was a frequent occurrence. Website visitors would often receive a warning stating that a catastrophic error had occurred (or similar), calling the user to download a certain software to clean or fix their device.

A message like this can be frightening to users who are unaware of the security risk or who have little knowledge of social engineering attacks. An anxiety-inducing message, such as the above, can intimidate or pressure a user into clicking the ‘Fix Now’ button before stopping to think. In downloading the software, the user actually installs a piece of malware designed to steal their data.

Mid 2000s – 2010s: Encryption-focused ransomware

Ransomware was largely focused on encryption between the mid 2000s and mid 2010s due to the changing societal landscape of profits, protections, and culture. During this time, there was significant development into how best to encrypt files on a computer to ensure that decryption was impossible.

According to the Anti-Phishing Working Group, instances of scareware packages rose from 2,850 to 9,287 in the second half of 2008. Then in 2009, the APWG identified a boom of 585% increase in scareware programs. Many of these scareware packages included ways to download ransomware that would be used to encrypt various pieces of data on machines.

In 2006, a piece of ransomware called Archiveus encrypted a number of users’ files and set the decryption password at 30 digits long. However, the geniuses at Sophos cracked the password, meaning the sample would forever be decryptable unless the method of encryption changed. Unfortunately for them, the attackers associated with Archiveus would not get paid – but at least they tried.

Future ransomware creators would learn several lessons from Archiveus. Firstly, their method of payment was to send a user to an online pharmacy and buy something from the store – which doesn’t scream anonymous to us. In addition, Archiveus only encrypted files that were saved in the My Documents folder. While this folder would contain valuable data, it would not cause maximum disruption, which is the aim of many of today’s ransomwares. But without these lessons, the next generation of ransomware wouldn’t have become so brutal.

GPcode is another ransomware that was around in the early ‘00s. It encrypted files in any directory as long as they contained the file extensions .xls, .doc, .txt, .rtf, .zip, .rar, .dbf, .htm, .html, .jpg, .db, .db1, .db2, .asc, or .pgp. This method is still used today by modern ransomware and, because of its scope, is much more brutal than just targeting the My Documents folder like Archiveus did.

In just 18 months, GPcode undertook huge transformations because it kept getting decrypted by Kaspersky. Eventually, they implemented AES encryption, but not in the best way. Kaspersky released decryption software the same day the new sample was released – impressive, because the key size was 660-bits, which would take a normal modern computer around 25-30 years to crack. This again paved the way for modern ransomware creators, who now use AES symmetric encryption with key sizes of at least 1024-bits to ensure files are irrecoverable after encryption.

But wait! There’s still more to ransomware’s evolution.

2010s

Ransomware pottered along for the next few years, growing in usage and hype, but it wasn’t until the mid 2010s that it hit the mainstream.

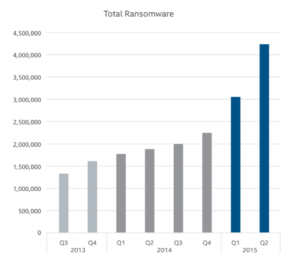

The third quarter of 2011 saw a huge spike in the discovery of malware samples, but despite this fast incline, the term wasn’t mentioned once in McAfee’s 2011 Fourth Quarter Threats Report. It wasn’t until 2012 that security companies started to discuss ransomware as a significant threat. According to McAfee’s 2012 Second Quarter Threats Report, there was a massive decline in fake antivirus software (scareware) and a huge incline in ransomware, probably due to a change in culture. Law enforcement came down hard on credit card skimming during this time, making it increasingly difficult to sell these personal financial numbers online. Hence, malware authors and threat actors moved to a more lucrative and destructive means of gaining money. By 2015, there were over 4 million samples of ransomware in the wild.

The ransomware families

Malwares often develop from the same or similar source codes, usually identifiable by meaningful strings or letters inside the malicious file used to infect devices. In this way, malware can be compared to organized crime, with families that control numerous operations in various criminal sectors.

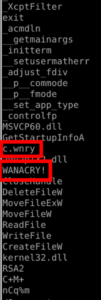

No blog about ransomware would be worth its salt without mentioning WannaCry, a ransomware that hit the NHS in 2017. Its binary code contained unique strings which may have had a part in naming this infamous malware. However, some people wrongly believe it was named in such a way because the ransomware would make you ‘want to cry’ after all your files become encrypted.

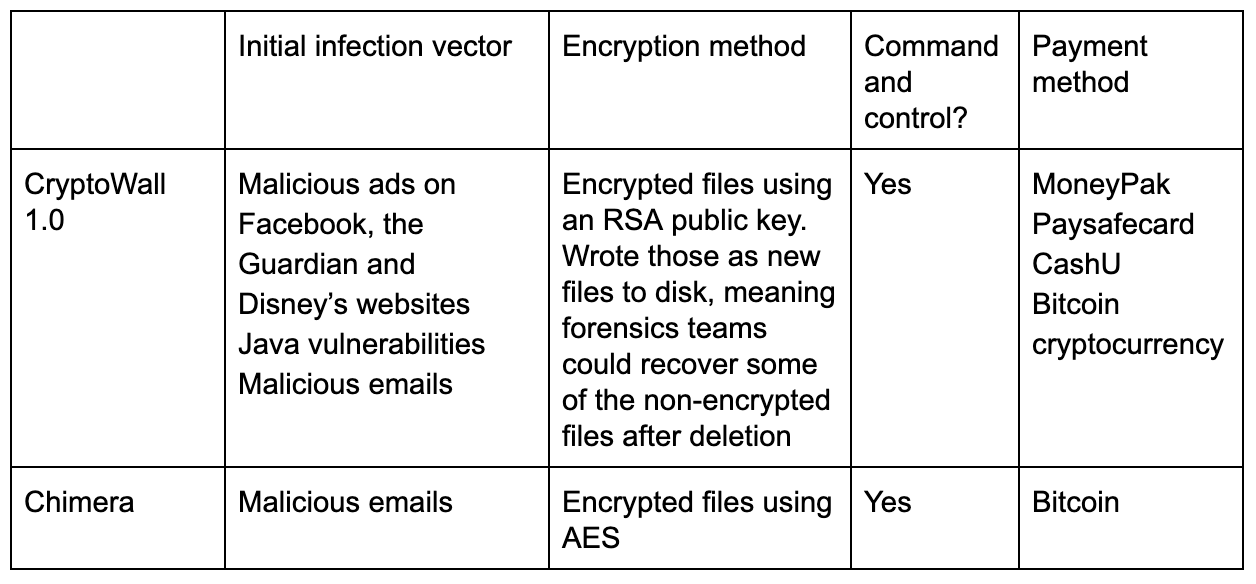

Between 2011 and 2015 some malware families started major operations of distribution and began attacking various companies around the world. This kicked off the vitalization of ransomware and the number of discovered samples began to skyrocket. There are two important crypto families worth mentioning at this time in ransomware’s evolution: CryptoWall and Chimera.

The former saw many revisions throughout 2014 and 2015, finalizing four different versions that remediated previous issues. Chimera meanwhile was a big ransomware sample in 2015, used to locate and enumerate network connected drives and encrypt many more files than most ransomware families had before. It renamed encrypted files with the file extension ‘.crypt’ to determine and keep track of affected files. Chimera was conscious of not encrypting important system files, so it tended to omit particular directories such as \Windows, \$Recycle.bin, \Microsoft, \Mozilla Firefox, \Opera, \Internet Explorer, \Temp, \Local, \LocalLow, and \Chrome.

Late 2010s: Ransomware as a service

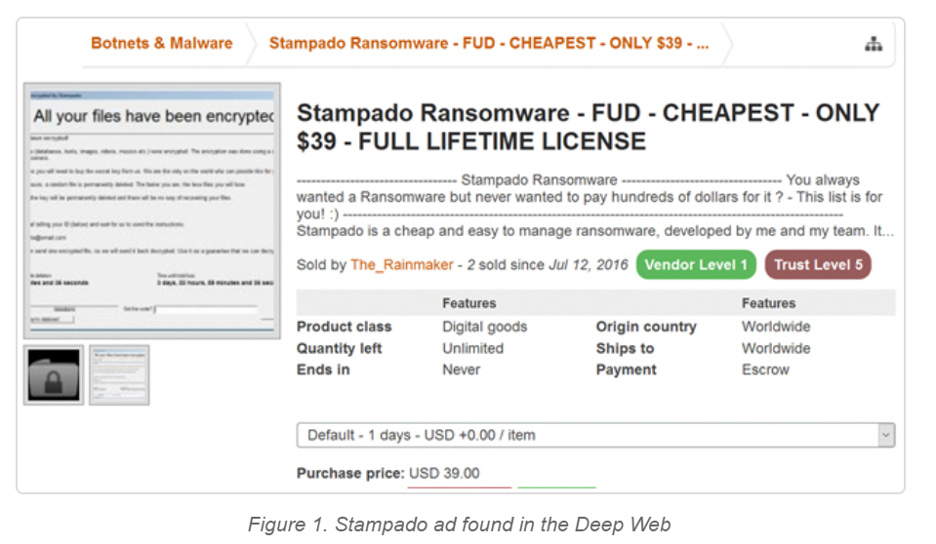

New families of ransomware reportedly rose 172% in the first half of 2016. As it increased in value, it was only natural for ransomware to become a commodity. Since late 2015 there has been an uprising of ransomware as a service (RaaS), where threat actors sell variants of ransomware to anyone who wants it – sometimes for as little as $39. It is a lucrative business and has such a low entry barrier that practically anyone can begin infecting companies.

RaaS is a way for malware authors to find new, additional forms of income. While the earlier variants of RaaS charged for full-time licenses, modern day RaaS variants take a percentage of the infection profits.

Furthermore, to stop FBI agents and law enforcement interacting with the hackers through marketplaces, variants including Sodinokibi (owned by a group called REvil) and a predecessor, Gandcrab, work as affiliate programs. Hacker groups operate the infrastructure, configure payment methods, and keep the malware up to date, while the affiliates infect and distribute the malware. These hacking groups would then take a percentage of the ransom, normally between 30-40% if a certain number of machines were successfully infected and the ransom was paid. Affiliate programs make ransomware profitable to anyone – from script kiddies to large criminal organizations.

WannaCry was an incredibly high profile attack that brought ransomware to the forefront of most media outlets. Although the code itself was written poorly, it played a huge part in introducing ransomware to the mainstream. If you want to understand what WannaCry looks like and analyze its inner workings, try these labs.

2020s: Extortion-focused era

That brings us to the present day, an era of ransomware that tends to focus on extortion. Many current ransomware authors have learned harsh lessons from past mistakes, including aspects of encryption, methods of extortion, and financial gains.

There are frighteningly brutal new ransomware variants being released every month, breaching larger corporations with each hit. In 2020, Travelex, Honda, the NHS, and other huge organizations have fallen victim to new types of ransomware. So how have they changed?

Firstly, modern day encryption is virtually unbreakable. Thanks to RSA and other encryption methods, often, if implemented correctly, files simply cannot be decrypted within a reasonable time frame. For example, if a file was encrypted using an RSA 2048-bit key – as seen in Maze ransomware – it would take a standard laptop 300 trillion years to break.

Fun fact: quantum computing is said to be able to break this encryption in 10 seconds.

However, these attack groups have now moved away from simply dropping ransomware on a machine, encrypting files, and waiting for the money. They have completed the encryption side of ransomware, and can’t make it much better. They need a new focus.

Now and increasingly often, attackers are targeting and actively pressuring companies by exfiltrating files before encryption and threatening to publish data or documents online. While this wasn’t invented by the new modern day variants, they have brought it into the limelight. Snake, Maze, and Sodinokibi are variants being discussed almost daily in the news in 2020, but what they have in common is the pressure they apply to the extortion phase of the attack. It’s almost like they’re following the Lockheed Martin Cyber Kill Chain!

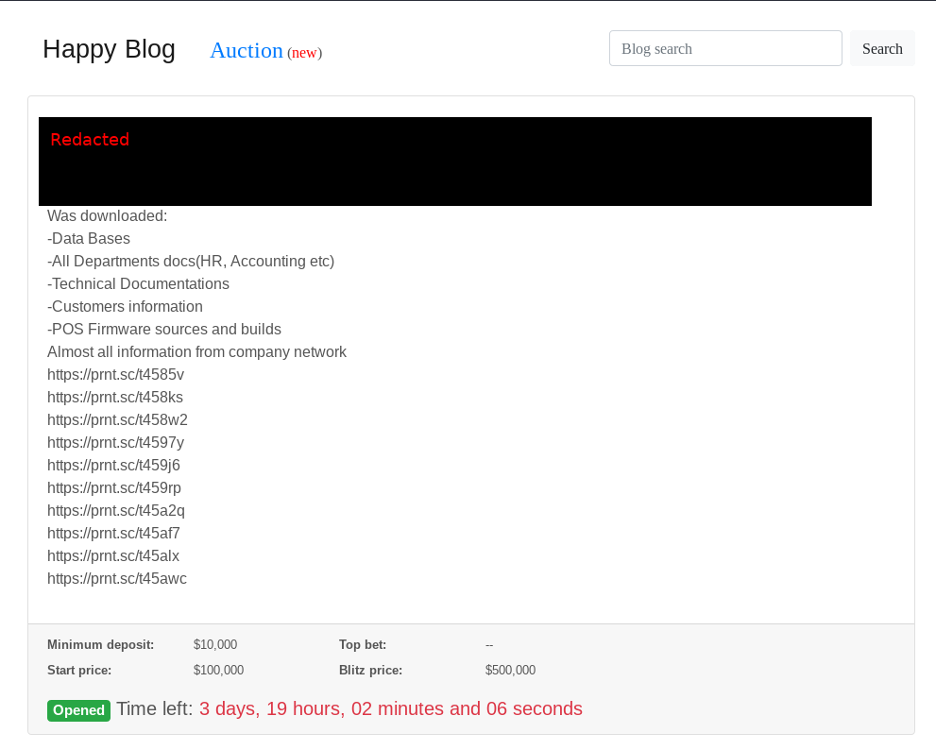

For example, the Sodinokibi masterminds REvil have their own Happy Blog, on which they release sensitive data about companies who do not pay their ransom. On the site, they charge for the files they have in an attempt to make maximum profit.

| Initial infection vector | Encryption method | Command and control? | Payment method | Exfiled data? | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maze | Malicious email, exploit kits, RDP brute force | Encryption files using RSA-2048 and ChaCha20 | Yes | Bitcoin | Yes |

| Dharma | Malicious email, RDP brute force | Encrypted files using RSA-1024 and AES-128 | Yes | Bitcoin | No |

| Snake | Malicious email, RDP brute force, Exposed vulnerable systems | Encrypted files using RSA-2048 and AES-256 | Sometimes | Email an address for further information | Yes |

| Sodinokibi | RDP brute force, Malicious documents, Exposed vulnerable systems, Drive by compromise on websites | Encrypted files using AES and Salsa20 | Yes | Bitcoin | Yes |

The table above visualizes the many similarities between the ransomware families. Their operation methods, styles of encryption, and payment facilities are all pretty standard, having fully evolved from the days of 2006 when the ransom had to be paid via an online store. It seems there’s almost a code of best practice for ransomware creators to follow now, of which the steps include:

- Correct encryption

- Standard file extensions to be encrypted

- Bitcoin payment method

- Maximize extortion potential

One aspect that has changed little is the use of malicious emails to distribute the ransomware. This technique was utilized by malware distributors back in the mid ‘00s and is still prolific today. Clearly, it’s an effective technique to initiate breaches!

Finally, one important understanding is that newer variants of ransomware have an RDP brute force infection vector in common. This particular type of infection has seen a huge rise in the past few years and a major jump in 2020. This might be due in part to the Covid-19 pandemic. The virus has meant that companies have quickly had to implement remote working strategies, opening up their internal networks for employees to access from home. This culture shift, or societal change in the way we do things, has meant threat actors are adapting their methods to better suit a larger attack surface.

Timeline

Conclusion

Ransomware has evolved so much that it’s hardly recognizable from Dr. Popp’s first known variant. Threat authors have come so far that the landscape looks increasingly gloomy, but there are several ways you can prepare yourself and limit the impact of these sophisticated attacks should ransomware hit your network.

Awareness

Immersive Labs has released labs on understanding the tactics and techniques used by these new ransomware families. This is perfect for any defensive security team to gain an understanding of how the malware works in a sandboxed environment. We’ve also created labs based on investigating real-life attacks so teams can exercise against these latest threats, ensuring their networks do not fall victim in the future.

Patch

Understand what your external infrastructure looks like to the internet and what attackers can see. Keep that infrastructure up to date and correctly implemented.

Training

Your entire company should understand the common ways these attacks start, as they will target everyone. Keep your staff updated with knowledge on the latest threats and what to do when they occur. One way to do this is by using our Cyber Crisis Simulator, where anyone can access a simulated crisis exercise, view and analyze results, and test incident response teams.