The Havoc command and control (C2) framework is a flexible post-exploitation framework written in Golang, C++, and Qt, created by C5pider. Engineered to support red team engagements and adversary emulation, Havoc offers a robust set of capabilities tailored for offensive security operations.

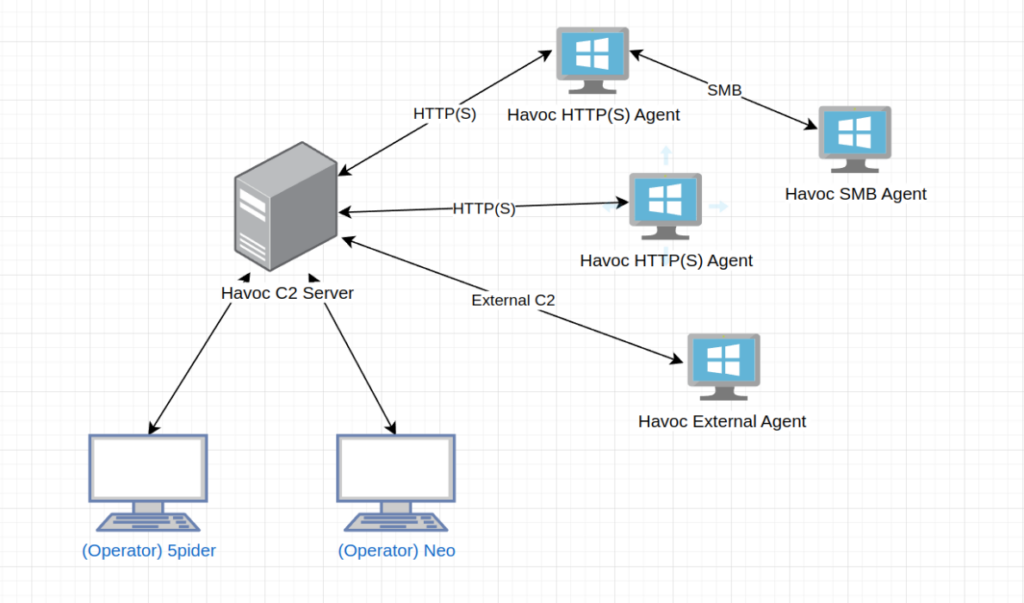

Havoc was first released in October 2022, and is still under active development. At the time of writing, Havoc supports HTTP(s) and SMB as a communication protocol for the implants. Havoc’s ability to generate payloads, including exe binaries, dll files, and shellcode, appeals to threat actors seeking a malleable and simple post-exploitation framework for their campaigns.

This research aims to empower defenders to detect the presence of Havoc, analyze its proprietary agents, known as Demons, and enhance organizational resilience against modern post-exploitation attack flows.

In the wild

Havoc is open-source, simple to use, and has little defensive-focused coverage, making it a popular option for adversaries. Over time, it’s likely to grow even more popular, particularly as other tools like Cobalt Strike already have extensive defensive coverage. Some organizations like ZScaler, Critical Start, and The Stack have analyzed Havoc demons actively used in the wild targeting government organizations.

Between Q4 2022 and Q1 2023, Havoc coverage increased as it could be used to bypass the latest version of Windows 11 Defender. Threat actors have since utilized Havoc, leveraging third-party tools and plugins to bypass AV and EDR solutions, enhancing their flexibility in attacks.

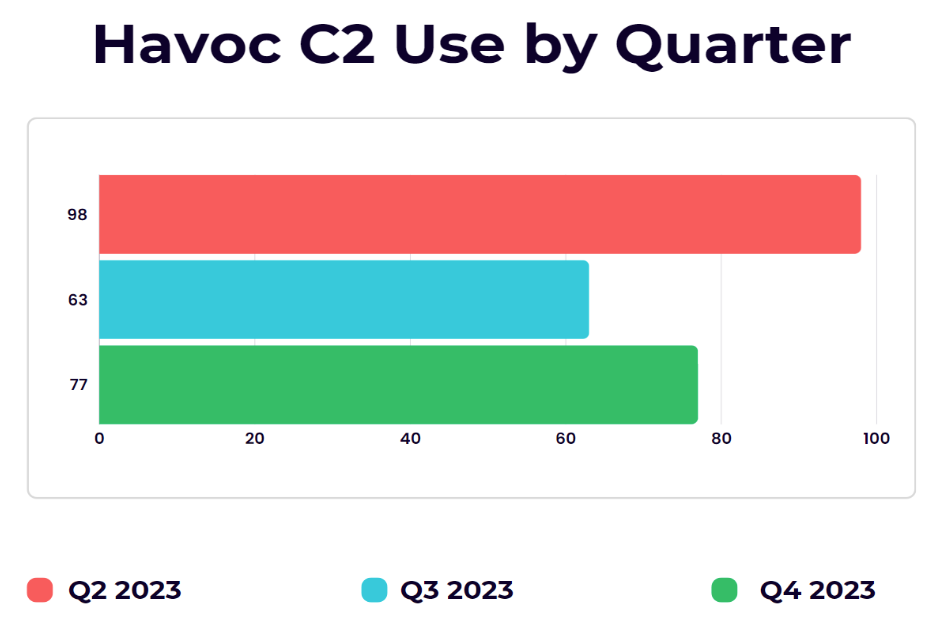

Between Q2 and Q4 2023, Spamhaus released its Botnet Threat Updates report, revealing a 22% increase in the use of Havoc as a backdoor during that period. The graph below represents the total change in the use of Havoc throughout 2023.

There was a 36% drop in use between Q2 and Q3 2023. This decline may be attributed to the waning novelty of bypassing Defender, as Microsoft consistently updates its security measures to safeguard users against emerging threats. Toward the end of the year, there was a 22% increase in Havoc usage. This trend suggests that with ongoing updates to Havoc and extensive research into other C2 frameworks, Havoc will inevitably be used more by threat actors.

This graph was created and informed based on the Spamhaus Q2, Spamhaus Q3, and Spamhaus Q4 2023 threat reports.

Threat hunting

Because defensive coverage isn’t very common right now for Havoc, it’s important that defenders understand Havoc’s capabilities and equip themselves with the knowledge of detecting and analyzing Havoc, including its traffic and generated artifacts. The Immersive Labs Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI) team has closely examined Havoc and identified methods for incident responders to obtain both host-based and network-based indicators of compromise (IoCs).

This report details these technical findings and the detection engineering process used to discover them.

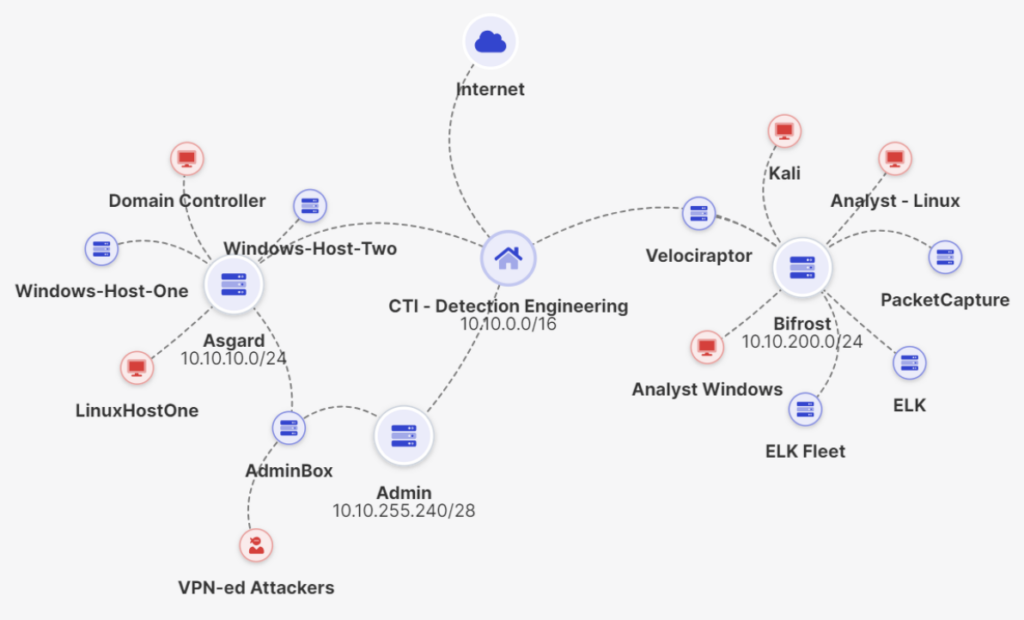

The range

To capture all of the traffic and artifacts necessary for analyzing the Havoc agents, we first set up a specialized range made for detection engineering with high-fidelity log collection and EDR capabilities. This was deployed using an Immersive Lab’s Cyber Range template. You can achieve the same outcome by manually deploying your own infrastructure, following Havoc C2’s documentation, and reading this report.

The range had the following essential components:

- An external host machine to deploy the agent (playing the attacker role)

- Event logging

- Sysmon

- Elastic

- Network logging

- Full packet capture

- DNS logging

- TLS secrets

- EDR

- Velociraptor

- Reset/restore

Attacker’s infrastructure

With our defensive range, called Heimdall, in place, we then had to deploy the attacker’s infrastructure. All that was required to run Havoc was a Kali Linux instance on a public IP address. Ubuntu 20.04/22.04, Debian-based distributions, Arch distributions, and MacOS also work, though the steps to installing and setting up Havoc will differ based on the distribution you use. The Havoc installation documentation covers these differences. A single AWS EC2 (or similar) instance on a public IP address is all that’s needed, making it easy to open the required TCP, HTTP/S, and DNS ports to the range.

Havoc teamserver

The Havoc C2 framework is split into two components: the teamserver and the client. The teamserver handles connected offensive operators and manages the listeners, along with callback parsing and the downloading of screenshots and files from the demon (agent). The client side is the user interface that operators will see; operators can task the agent and receive outputs, such as command outputs, or loot. Loot is a term defined by Havoc and includes screenshots and file downloads.

For more details on how to use Havoc, please refer to Havoc’s documentation.

Installation and configuration

Installation is pretty straightforward. Exact steps for installing, configuring, and creating payloads can be found in Havoc’s official documentation and GitHub repository.

Obtaining the encryption keys from the teamserver and database

Our research aimed to identify reliable and repeatable ways to obtain encryption keys. Reverse engineering a demon yielded no actionable results. We needed a way to determine what the keys were, so they could be used to decrypt and examine memory and network traffic.

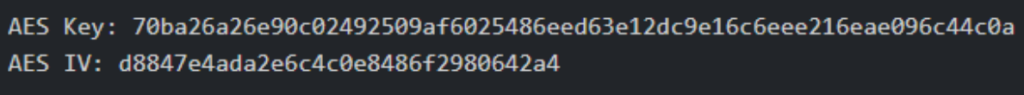

To that end, we adopted the same technique we used in our Sliver C2 research. Because Havoc is open source, we identified the source code responsible for generating the encryption keys and added print statements to the code.

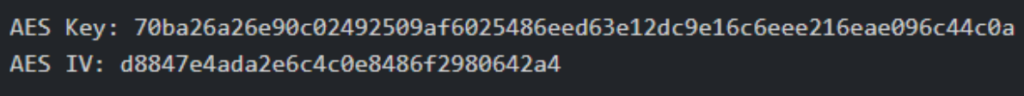

Upon modifying aes.go, recompiling the teamserver, and running the demon, the keys were printed as standard output.

Now that we knew what the keys were, we used this knowledge to develop a methodology for obtaining the keys from packet captures and memory dumps.

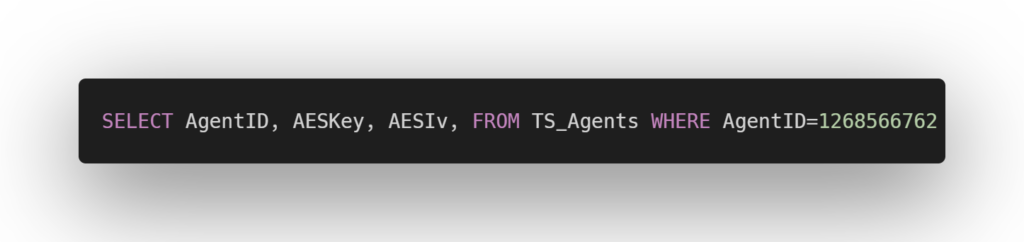

Another method we found was to obtain the keys from the database using SQLite. This involves running sqlite3 from teamserver.db, and running the query below, replacing the AgentID with the agent ID of your demon.

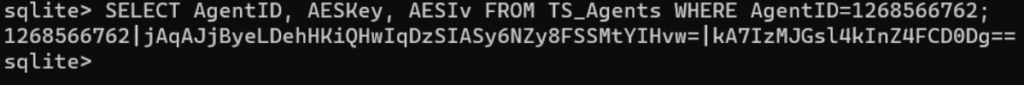

The output below shows the Key and IV, but they are Base64 encoded.

After decoding, we get the keys.

These keys differ from those previously shown because we used two different demons to test these methods. However, using the methods described above will always print the keys.

Obtaining the encryption keys from packet capture

Having obtained the keys, we then developed a methodology to help defensive operators acquire them from both packet capture and memory, detailed below.

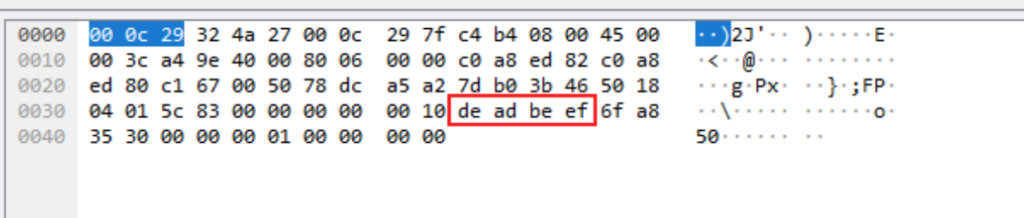

After setting everything up, we ran the demon on the target machine with Wireshark packet capture enabled. This allowed us to monitor all the HTTP and TCP traffic between the demon and the teamserver.

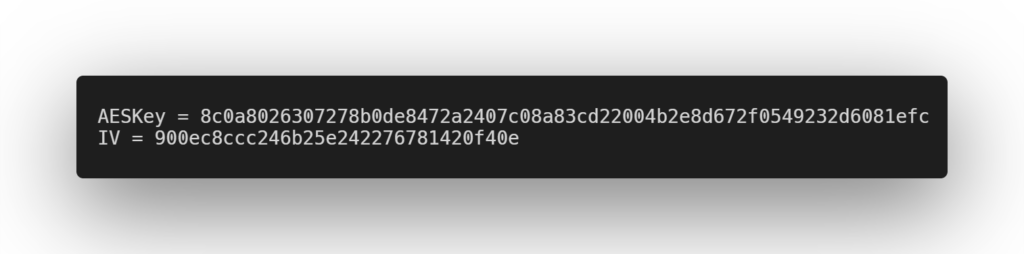

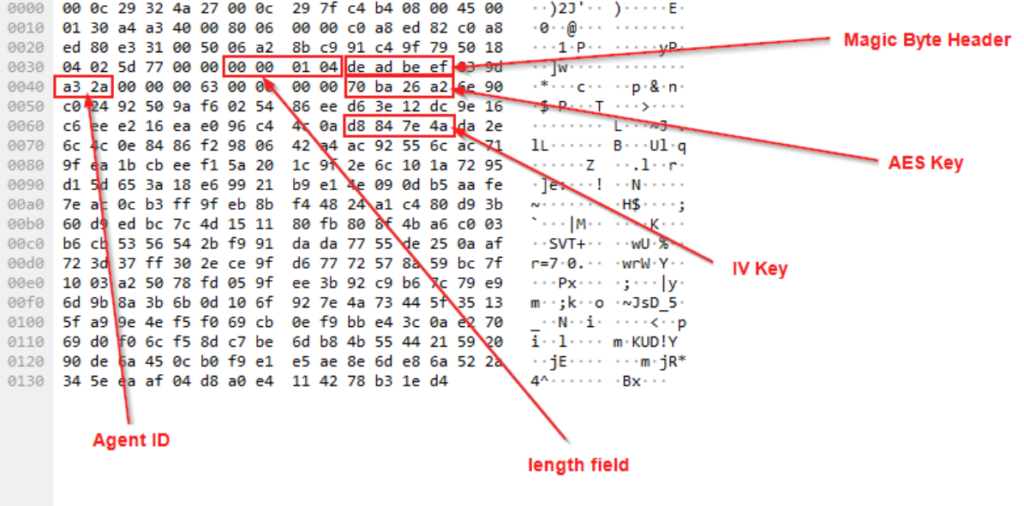

Upon analyzing the first packet in the capture, we noticed that the first bytes said dead beef, which is a magic byte value, shown in the red box in the picture below.

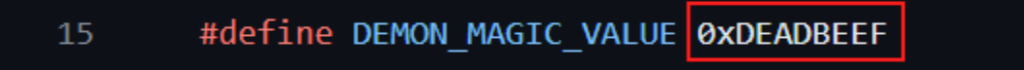

Upon checking the Havoc C2 GitHub repository, we identified the definition of the 0xDEADBEEF magic value, found in the Defines.h file.

Havoc uses a standard polling technique known as beaconing, where the agent checks in with the teamserver at regular intervals. This interval is set by the C2 operator as a sleep time value. Identifying C2 communications in packet capture can be characterized by identifying this beaconing behavior.

For Havoc, the request to the server contains the response from any commands or a request for any jobs. The response from the server to the client contains the next task the implant is being instructed to execute, for example, to run a shell command.

Going further through the packets, we see continuous communications of a POST request and an HTTP status code 200 acknowledgment. This is a transmission where the demon checks in with the teamserver. These are continuous requests; their cadence is dictated by the sleep time set on the agent, where it encrypts itself in memory to avoid detection.

![]()

The default sleep value is two seconds, but this is easily changed by the attacker. To avoid being detected in memory by EDRs, Havoc implements a sleep technique that encrypts its own payload in memory. These sleep techniques include:

- Foliage – Creates a new thread, using NtApcQueueThread to queue a return-oriented programming (ROP) chain, encrypting the demon and delaying execution.

- Ekko – Uses the RtlCreateTimer to queue an ROP chain that encrypts the demon in memory, delaying its execution. This technique has a GitHub repository.

- WaitForSingleObjectEx – No obfuscation, just delays execution for the time the sleep is set for, default is two seconds.

Going through the packets in the capture, and using Wireshark’s filter feature, we filtered on hex, searching for the encryption keys we got earlier from the teamserver. We also identified the agent ID, correlating this based on it being shown in the teamserver. This pattern has remained consistent with multiple tests with different agents using different sleep technique configurations.

The encryption keys appear to be sent in the first non-check-in HTTP POST request from the agent to the teamserver, shown in the picture below, along with the magic byte header, agent length, and AgentID.

Decrypting traffic

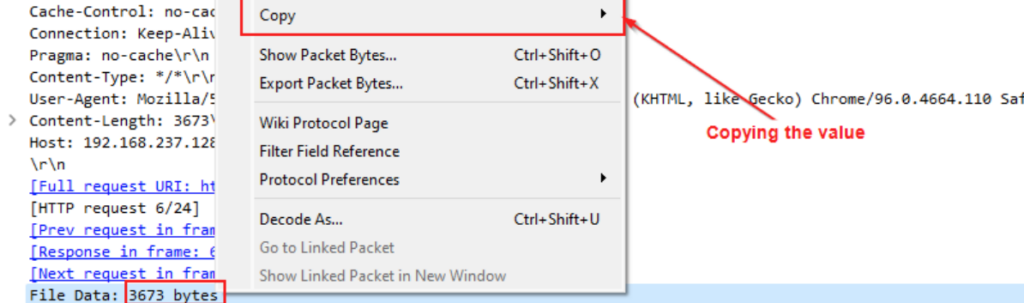

To identify the location of the traffic, we had to identify packets with a length that would dictate something more was happening than a check-in or sharing of keys. We identified a POST packet with a length of 3673 bytes, which was the largest packet so far. At this point, we could only guess that this was a command. We needed a way to validate this hypothesis.

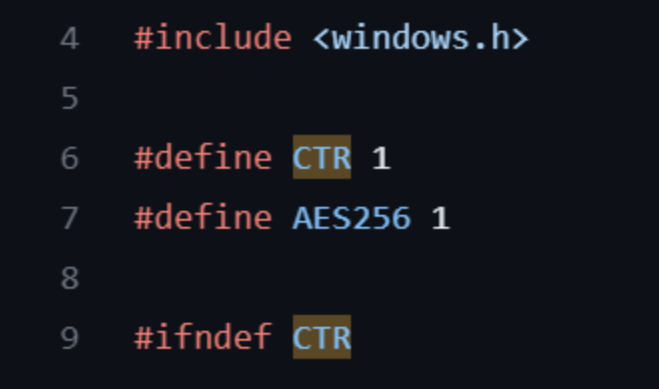

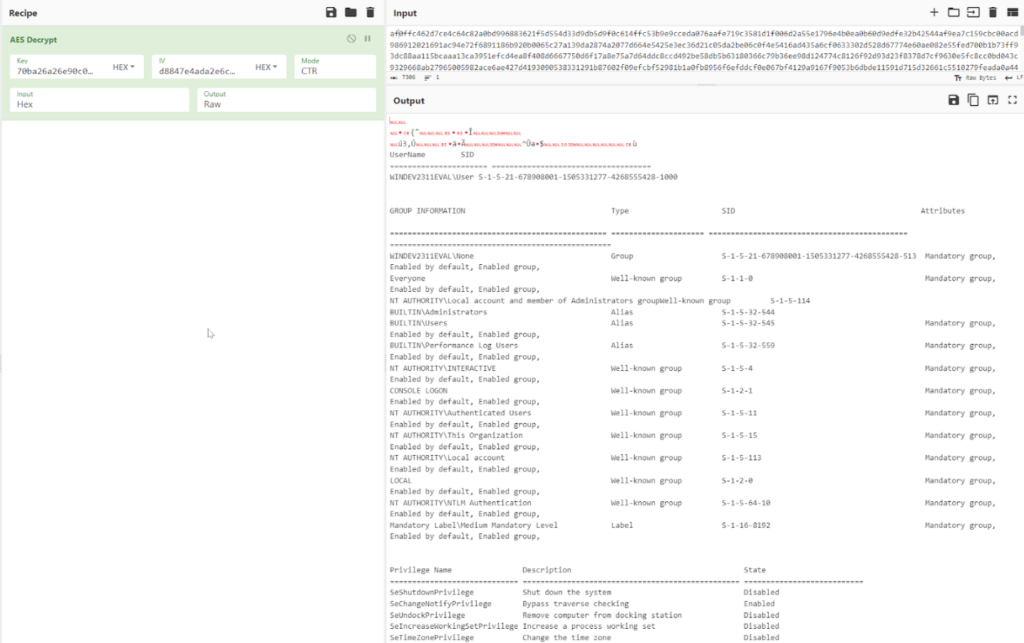

We did this by copying the value and bringing it into CyberChef so we could attempt to use the keys to decrypt it and potentially see a command output. For CyberChef, we needed the encryption method (AES256), the key, IV, and the mode, which we knew was CTR, since the AESCrypt.h file from Havoc’s GitHub repository indicated as much.

Adding these to CyberChef and decrypting got us nothing, until we started removing bytes one by one from the beginning of the input, the picture below shows the command output that gets sent to the teamserver.

The image below shows the rough location where the beginning of the output is located, based on the CyberChef output.

The natural direction to go from here would be to try to discover commands in the pcap; however, this isn’t possible as they are sent via beacon object files (BOFS). The only known way to discover what commands an attacker used is to capture and decrypt outputs and draw an inference from them.

We identified a number of the commands being sent from the header field. However, a large number of features are implemented as BOFS, and all share the same command_id. This makes it difficult to understand the exact command being executed without analyzing the BOF, or the response. We have released a tool that can be found in the GitHub repos, which extracts and saves all sent BOFS and their responses if you have the AES key.

Obtaining the encryption keys from memory

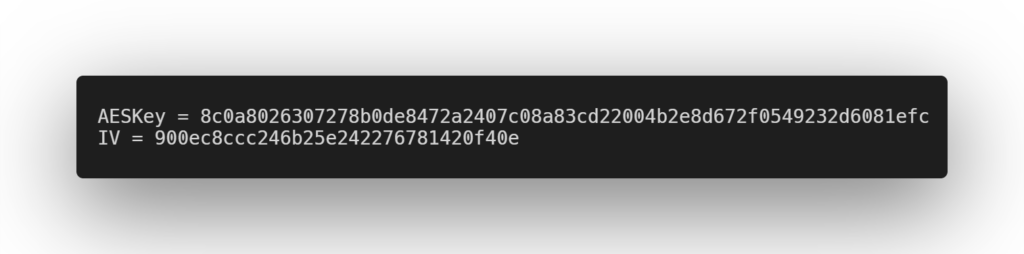

We started this process by grabbing the keys from the teamserver.db using sqlite3, as previously discussed in the ‘Obtaining the encryption keys from the teamserver and database’ section. We also went to the victim machine and dumped the memory.

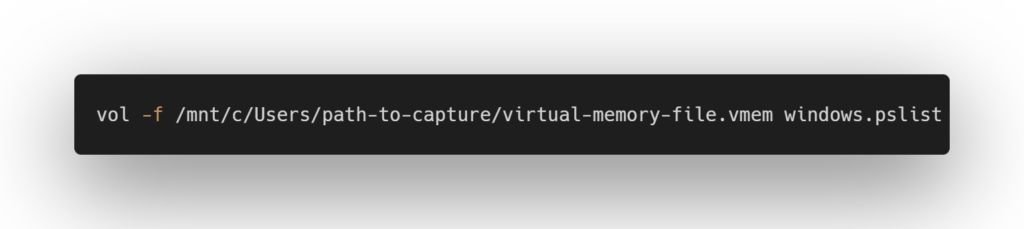

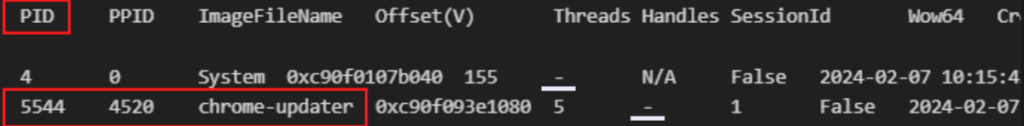

Then, we needed to find the process PID for our demon, called chrome-updater.exe, using Volatility. We did this using the command below against our memory dump file.

We can see the process PID is 5544.

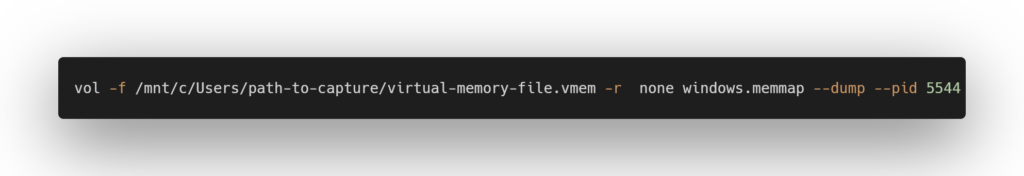

With the process PID in hand, we can then dump the process memory for chrome-updater.exe.

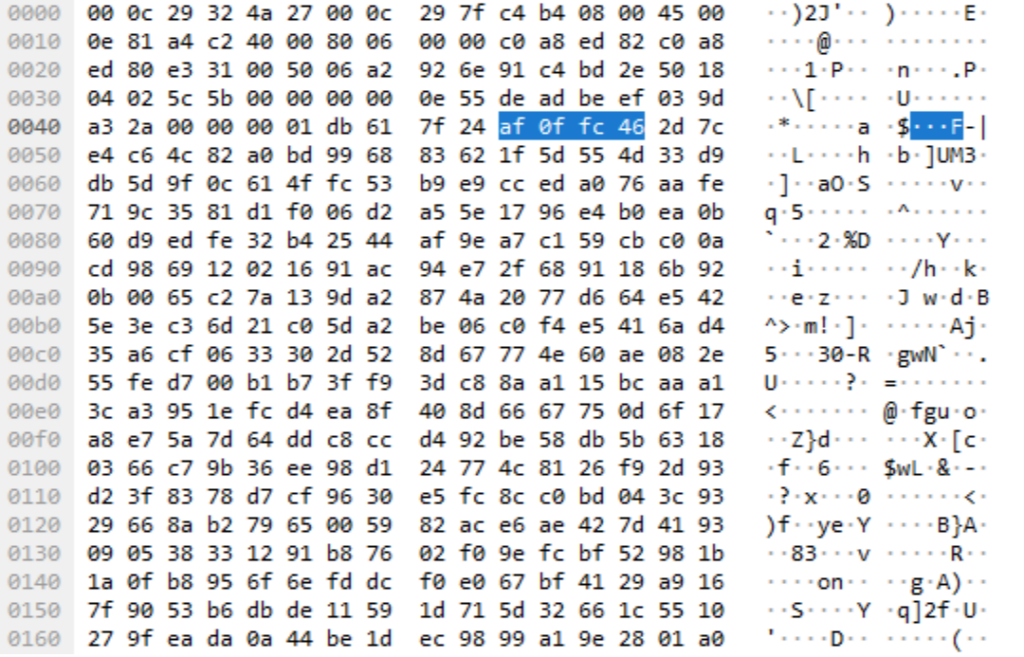

Next, we faced the memory dump for the chrome-updater.exe process. We opened it in a hex editor and began searching for the keys. We wanted to determine if the keys were present in memory and if they could be identified through a scannable, consistent structure.

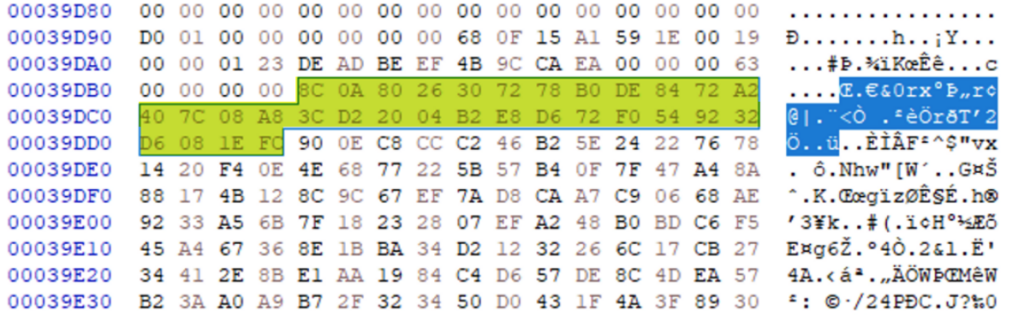

The answer to these questions is yes! We tested this a number of times and came to the same result, as shown in the picture below.

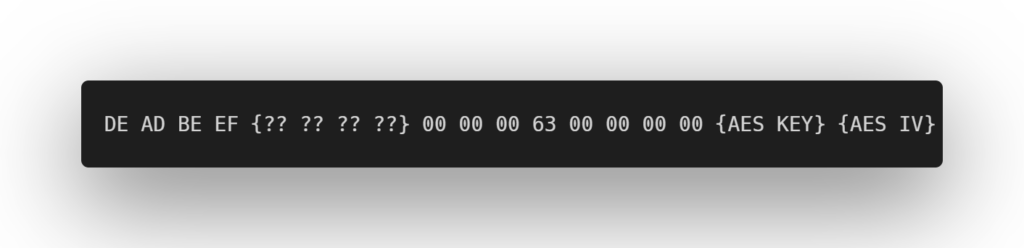

The structure is exactly the same both in memory and packet capture, specifically as below.

DE AD BE EF is the magic signature for Havoc, and while it can be modified in source, it is the default value. The next four bytes are actually the AgentID, and 00 63 is the DEMON INIT command sent from the client to the team server.

Detecting Havoc C2 in memory

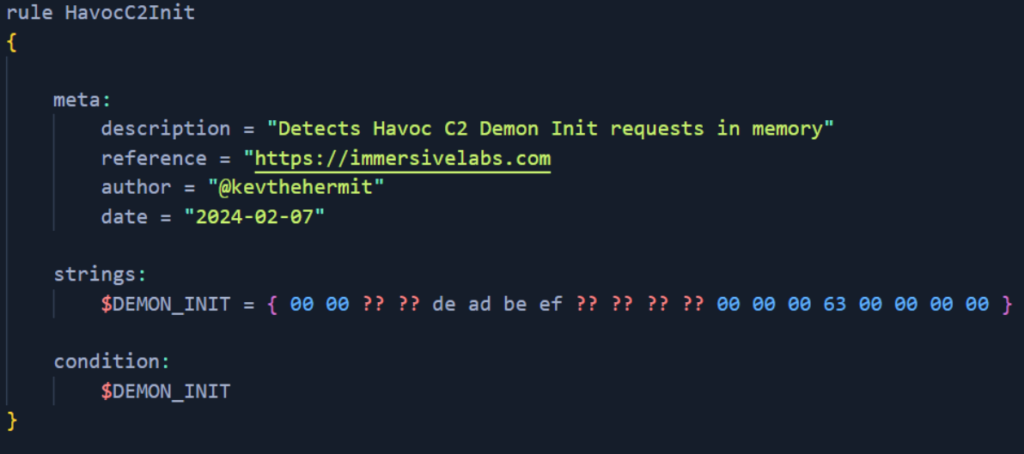

With a reliable method established for obtaining encryption and IV keys from packet capture and memory, a YARA rule was created to specifically detect demon INIT requests in memory.

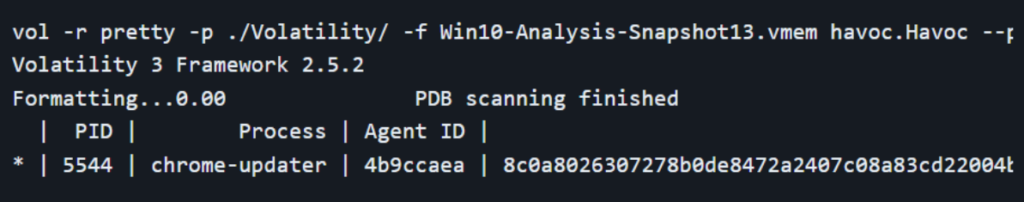

We have also created a Volatility plugin for detecting Havoc C2 in memory, which can be found in our GitHub repository. An example of the expected output is shown in the picture below. This structure isn’t deleted from memory, so rules could be run retroactively to identify Havoc agent actions.

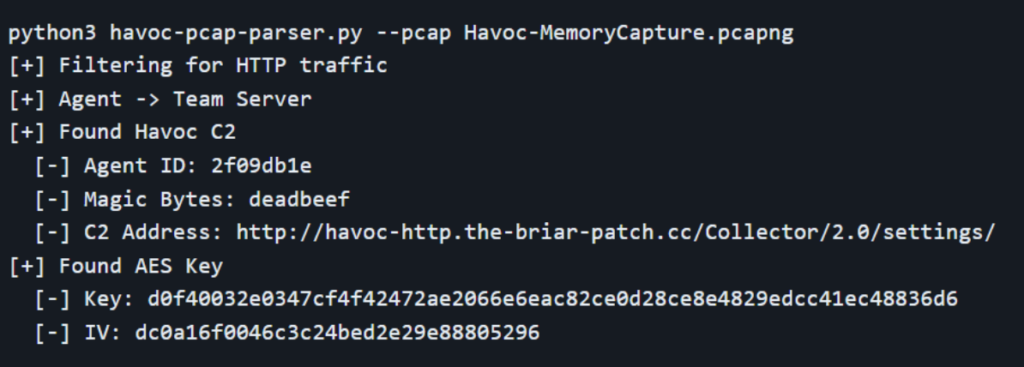

We have also created a Python script to parse Havoc C2 traffic from a packet capture. The requirements for use are in the GitHub repository.

The script requires either that the C2 traffic was sent over HTTP or that you can decrypt the TLS layer of the HTTPS traffic using something like TLS MASTER secrets. The Heimdall range is designed to save all these secrets for pcap decryption.

If you didn’t have the first packet where the encryption keys are, you could get the keys from memory, as previously discussed, and use them to decrypt the packet capture traffic.

An example of the expected output can be found below.

Detecting Havoc C2 in using SIEM

This was one area of the research that yielded limited information. As previously mentioned, commands sent from the teamserver to the demon are contained inside BOFS; searching for any indication of this communication in Elastic yields no actionable results.

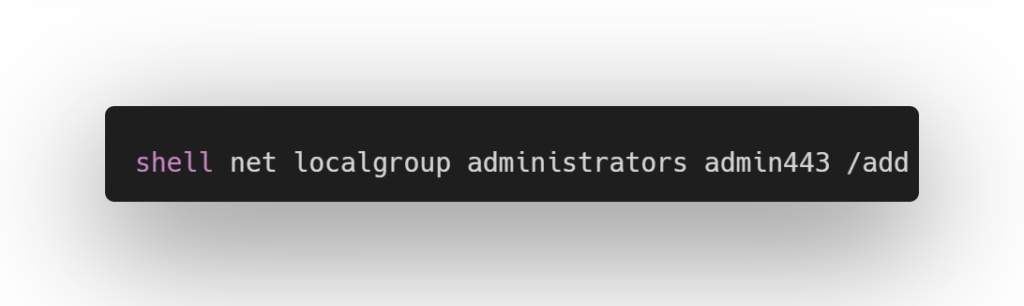

If an attacker chooses to send shell commands from the teamserver, such as the command below, you’d be able to pick it up in Elastic with PacketBeat enabled.

In the context of Havoc, a shell or PowerShell command is specified by the attacker, and this opens cmd [dot] exe or powershell [dot] exe, respectively. They then run commands on the target machine in the context of a local cmd [dot] exe or powershell [dot] exe session. Therefore, it would get picked up in Windows Event Logging, Security Logs, Elastic, or your SIEM of choice.

If an attacker opts for stealth, they’ll run their commands without a shell, therefore as BOFs. With our Elastic setup, we couldn’t retrieve details about commands executed and stored in BOFs. The only way we found to capture commands was if the attacker ran their commands to the agent through cmd [dot] exe or PowerShell, which they can specify from the team server.

Getting hands-on

If you’re an Immersive Labs CyberPro customer, you might enjoy our Havoc C2: Memory Forensics lab, a hands-on practical lab to test out the techniques in this research report.

The Immersive Labs CTI team also researched another C2 framework called Sliver. If you’re interested, check out the research blog post. If you’re a CyberPro customer, have a look at the lab Sliver C2: Memory Forensics. We also have a Team Sim called Detecting Sliver, for those with Team Sim licensing.

You can also find the detection engineering range without the addition of the attacker infrastructure in the Ranges Dashboard as the Heimdall Detection Engineering range.

To learn more about how Immersive Labs helps organizations assess, build, and prove cyber resilience, visit our Resources Center.